The ‘Gateway Drugs’ to Gambling: The Swedish Edition

Spelinspektionen's report into young people and gambling has thrown up some alarming data.

The Swedish Gambling Regulator, Spelinspektionen, has published a report taking a comprehensive look at how young people in the country engage with gambling.

The report notes that there has been an increase in gambling not only among 18-24-year-olds but also among those under the age of 18.

The post is split into four broad sections:

Loot boxes;

Skin gambling;

Casino streaming and influencer-led marketing;

For what it’s worth: my thoughts

The above are often interconnected and are understandably frequently considered ‘gateway drugs’ for traditional regulated or unregulated gambling.

TLDR:

Youth gambling on the rise – Gambling participation is increasing among both 18-24-year-olds and under-18s.

16% of 16-17-year-olds and 45% of 18-24-year-olds have purchased loot boxes, often seen as a gateway to real-money gambling.

Loot boxes mimic gambling – 62% of those who bought their first loot box before age 12 later gambled with real money before 18.

26% of self-excluded gamblers who had bought loot boxes early started gambling before 16.

Skin betting is widespread – 50% of young men surveyed had gambled with skins, with 62% of self-excluded gamblers having engaged in skin betting.

57% of skin bettors admitted to gambling beyond their financial means.

Gambling ads target young people – 75% of 16-17-year-olds saw gambling ads in the predating seven days.

45% of Instagram posts, 37% of Facebook posts, and nearly all YouTube videos from licensed operators were visible to minors.

Casino streaming fuels problem gambling – 76% of regular casino stream viewers admitted gambling beyond what they could afford.

An +More Media publication.

For sponsorship inquiries email scott@andmore.media.

Loot Boxes

Definition

The UK government has defined loot boxes as “features in video games which may be accessed through gameplay, or purchased with in-game items, virtual currencies, or directly with real-world money.”

Loot box rewards are often randomised, with certain rewards harder to obtain than others. The opening of a loot box is often engineered to be dramatic, and critics say they closely mirror ‘slot machines’ not only in aesthetic but also by encouraging users to spend continuously and incrementally to potentially obtain desirable outcomes.

Regulatory landscape

From a regulatory perspective, loot boxes and video games have been discussed more frequently in recent years. Countries such as Belgium have outright banned games that offer loot box mechanics. In contrast, the UK now has extensive guidelines requiring companies to disclose reward probabilities within games and other measures for the protection of minors. Protection has been ill-enforced, and little to no progress has been made (but that’s a whole different Substack).

Causation or correlation?

The report seeks to explore further a causal link between loot boxes and potential gambling harm.

Swelogs 2021 report:

16% of 16-17-year-olds had purchased loot boxes in the last year

Swedish Public Health Agency youth survey:

14% of 16-17-year-olds had bought loot boxes

16% of 18-19-year-olds had bought loot boxes

Spelinsektionen Survey:

45% of young adults (aged 18-24) had bought a loot box at some point in their lives

The gambling authority has suggested that, given that the survey targeted individuals who had gambled for money in the last year, the discrepancies between the three surveys are unsurprising.

Is it just loot boxes?

The 2021 Swelogs report also attempted to measure the correlation between loot box spending and having symptoms of problematic gambling.

Those between the ages of 16 and 17 who had purchased loot boxes but not gambled for real money predominantly intended to gamble when they turned 18.

Similar tendencies were measured among individuals who played computer games for over three hours daily. After the data was controlled for gender and age, the relationship disappeared, suggesting that the correlation was specifically related to loot boxes rather than gaming in general.

A link to gambling harms:

The survey from the regulator revealed that:

62% of those who had bought their first loot box before the age of 12 undertook real money gambling before the age of 18;

26% of those who used Spelpaus (Sweden’s self-exclusion service) and bought their first loot box before the age of 12 started gambling for real money before the age of 16.

16% of the corresponding proportion in the remainder of the survey had participated in real-money gambling before 16.

All male respondents admitted experiencing the ‘chance’ to make a purchase within a computer game.

One respondent compared the rush from opening loot boxes to the feeling of playing at a Blackjack table. He commented in the interview, “Yes, that was actually a bit early. It was when I actually wasnt allowed maybe, but it was also for that little rush. It was probably mostly the rush.”

Further research from Spelinspektion delves into the potential link between microtransactions in computer games and real-money gambling. It specifies that loot boxes are ‘particularly significant’ for the following reasons:

Loot boxes offer random rewards, which may maintain interest and create anticipation among players;

As described by a respondent, the opening of a loot box can be designed to give a rush or feeling of excitement;

Game design, for example, having to open or purchase a loot box within a specific time frame forces a decision to be made quickly;

Seeing influencers or other players open loot boxes can also influence participation.

The research suggests that the above characteristics can also be found in real money games.

In interviews conducted by Spelinspektionen, respondents were asked whether they believed that purchasing loot boxes increases the likelihood of later gambling for money. Every respondent who said they had purchased loot boxes affirmed this assertion.

Skin betting

Definition

Skins are often obtainable through loot box mechanics, as described above. Skin gambling involves using skins as stakes or depositing skins to receive a ‘virtual currency’ that can be used to wager. When referring to skins for gambling purposes, the skins are all from Steam titles Counter-Strike, Dota 2, Rust and Team Fortress 2.

Skin betting sites now often offer a full sportsbook service, esports betting, lotteries (case battles), and various casino games (Crash, Plinko, etc). Balances are then withdrawable in skins, which can be sold back to Steam to increase Steam Wallet balance (not withdrawable) or sold on third-party websites for cash.

What the survey suggests:

The study suggests underage people who participate in both skin gambling and traditional gambling are likely to have an increased risk of developing gambling problems.

One of the respondents to the Swedish Gambling Authority expressed his view that those who engage in skin gambling are also gambling for money:

"I don't know anyone who isn't a player who does that. They spend a lot of money on online casinos. So that's quite a lot of money on online casinos and often. It's the same group."

(T, 21 years old)

The link between loot boxes and skin betting was further emphasised by another respondent:

"What you got in these loot boxes could be skinbetted. Then, there is also a market where you can buy and sell skins. Sometimes you bought skins, and then you had to pay a little more for the good stuff."

(J, 21 years old)

In the 2021 Public Health Agency's survey on young people and gambling, 6% of respondents in the 18–19 age group and 8% in the 16–17 age group had participated in skin betting.

In Spelinspektionen’s survey, skin gambling was far more common:

The results showed that nearly 50% of men (who had not enrolled in Spelpaus) had gambled using skins.

A vast majority of the men in the Spelpaus group had participated in skin gambling.

The percentage of women who had experience of skin betting or were aware of the phenomenon was significantly lower.

Skin betting, the gateway drug

Both survey results showed that a high proportion of those who had played with skins at some point had also gambled for more than they could really afford (57%) compared to those who had not used skin betting in the past 12 months (31%).

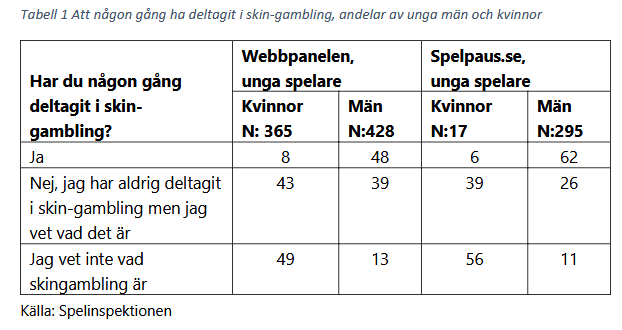

The above table, when (roughly) translated, shows the results of skin gambling participation among those who participated in the survey.

Of the females who had not used Spelpaus:

8% had participated in skin betting;

43% had never participated, but knew what it was;

49% did not know what skin gambling was.

Of the males who had not used Spelpaus:

48% had participated in skin betting;

39% had never participated, but knew what it was;

13% did not know what skin gambling was.

Of the females who had self-excluded:

8% had participated in skin betting;

39% had never participated, but knew what it was;

56% did not know what skin gambling was.

Of the males who had self-excluded:

62% had participated in skin betting;

26% had never participated, but knew what it was;

11% did not know what skin gambling was.

Influencer-led marketing and casino streams

New marketing channels for games were found to be reaching and attracting both minors and young adults.

You don’t have to dig far…

A study in Sweden showed that accounts belonging to licensed gambling operators on social media in Sweden were largely accessible to those under the legal gambling age despite the marketing material not necessarily being specifically targeted at a young audience.

45% of Instagram posts were visible to minors;

37% of Facebook posts were visible;

1 out of 295 surveyed YouTube videos were not available to those under 18.

The 2021 Public Health Agency survey showed that 75% of the 16-17-year-old age bracket had seen a gambling advert in the last week, and 6% outlined that advertising made them gamble for more than they had intended.

Every single person interviewed by Spelinspektionen outlined that gambling advertising is something they see every day. Several people mentioned traditional media, whereas others said they often see marketing on social media platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, and on popular podcasts.

"I'm very interested in sports and listen to a lot of podcasts and stuff, and there are almost only betting companies that advertise themselves. They throw in that you can contact the helpline if you have problems, but it becomes most romanticized by games. Often it can be that they interact with those who host the podcast and come up with tips on where you can play and when."

(M, 27 years old)

Watching streamers win big, makes you want to gamble

Tipping culture and influencer-led marketing are more recent phenomena. The report suggests that international research indicates that marketing through influencers has a noticeable impact on minors’ attitudes towards gambling and their intention to do so.

The report later details that the link between skin betting sites and influence via stream is clear to see. Spelinspektionen information showed that internet traffic to skin gambling sites from Swedish IP addresses gradually increased during 2023, peaking at 9 million visits in January 2024. At the time, there were approximately 30 Swedish-speaking influencers marketing them, mainly through Amazon-owned streaming platform Twitch.

In March 2024, the regulator issued a an on three gambling companies that provided games with skins in Sweden, and in mid-April a television broadcast went out reporting skin betting and casino streaming.

By the end of April 2024 “only a few” Swedish streamers still promoted skin gambling;

Traffic to skin betting sites decreased 60% by September 2024

Certain influencers resumed marketing, but started broadcasting in English instead of Swedish, which the authority suggests is to ‘circumvent the risk’ of being found to be targeting a Swedish audience and falling foul of regulatory guidance.

Key findings from the Spelinspektionen survey were as follows:

67% of those who had used Spelpaus had watched casino streaming in the past 12 months

58% of those on the ‘web panel’ had watched casino streams in the past 12 months

76% of people who watched weekly or monthly casino streams admitted they gambled for more than they were willing to lose

27% of people who did not watch casino streaming at all admitted the same.

For what it’s worth, my opinion

With any public health or gambling regulator-led (or actually any) survey, it’s imperative to take any findings with a healthy fistful of salt. Qualms about the size of the data pool, the specific people targeted (etc) can all be levied as valid criticism of the Spelinspektionen findings.

The results, however, do not really surprise me at all. I’ve long been a critic of the toxic slot-stream culture that sees hundreds of thousands of people typing “GAMBA” repeatedly as a streamer wagers hundreds of thousands (mainly through crypto) in a matter of hours. Chopping up highlight reels of big wins and putting them up on YouTube glorifies problem gambling, and while Twitch’s action to shift it from their platform certainly stunted the growth, Stake.com-owned Kick is often seen as nothing more than a hotbed for such activity.

Regarding skin betting, Sweden has a rich competitive history in both Counter-Strike and Dota 2, so the prevalence of skin betting is likely skewed to the higher end when compared to other countries. Skin betting sites are effectively offshore crypto sites too, operating under Curacao licenses - or occasionally under fictitious or no license at all. The API from Valve allowing third-party marketplaces to exist creates liquidity and ensures the practice continues - but Valve has shown little to no intent on properly ridding the scene of the practice. It’s a profit-generating machine and the company always absolves itself of the blame, pointing to terms and conditions which prohibit wagering activity.

Gambling regulators and governments can barely spell crypo, never mind regulate it - and when asked about video games, most of them would still peel back the monocle to tell you that Grand Theft Auto should be banned. We wouldn’t have any knife crime if that game had never come to fruition!

No one wants to take any responsibility over the mess of probability disclosures in mobile/video games and I could enforce the rules better from my parent’s shed.

It’s all a bit of a mess, and until someone gets a grip - the rest of the world will continue to look the other way and whistle - occasionally turning around to blame someone else.

Thanks for the comment, Petros. This is quite a common analogy, and there is definitely some truth to it. The issue, I think, comes from more of a Consumer Protection angle. I think the first point is that the digital nature makes it easier to spend in excess (this is a consumer protection concern, but fairly minor, in my opinion).

Many people have a more significant issue with loot boxes because of how they're designed and shown. They often have mechanics or visuals similar to slot machines (see a CS case opening where a wheel spins and stops on the skin). These items have a monetary value that can be traded through Steam/third-party marketplace. Some of the 'limited time' nature of loot box offers also give the payment/reward dynamic and encourage purchase within particular windows for a better chance.

I don't think putting loot boxes under gambling regulators is the answer. Still, correct probability disclosure and perhaps lessening the visual impact would steer people away from labeling them outright gambling products!

Thanks for the post. I have a question and I'm open to discussion: There's a lot of talk about loot boxes being considered gambling. But wouldn’t the same apply to Panini stickers or Topps cards? At the end of the day, they're just loot boxes in physical form. You pay, hope for the best, and tear open the pack, praying you've hit big.